Our house received an upgrade to full fibre optic last year, and with the increase in available home bandwidth came the opportunity to retire our old NetComm router/modem/WiFi unit, which had been, if we’re generous, “adequate”.

Or, in fact, inadequate in a number of ways – its WiFi range was actually abysmal, something I only found out when I migrated to a dedicated WiFi unit and discovered that a single device can actually cover our entire property.

Also, it “supported” IPv6, in the sense that it could, technically, have an IPv6 address for a brief period of time, before just quietly giving up on routing IPv6 traffic until you either reboot or get exasperated and switch off IPv6 support.

So in the spirit of questionable decisions, and egged on by friends who are far more skilled and experienced in this sort of thing, I purchased a cheap all-in-one fanless PC with four 2.5Gb ethernet ports.

For the curious, it runs at around 55 degrees in the Australian summer, 65 if I make the CPU think hard. Certainly an improvement over the poor old Mac mini I have running as an MPD server in our kitchen, which routinely idles at 80 degrees.

Because I can’t ever be content to do things the easy way, I put Proxmox on it first, with the intention of running OPNsense as a VM, alongside a PiHole instance.

My initial set up experience was tainted by an inability to get OPNsense to register a connection via the WAN port, which resulted in around 45 minutes of frustration before realising that my ISP requires me to manually “kick” connections between router changes. As a result of this faffing about, I now at least have a document detailing exactly what each of the physical ethernet ports are called in Proxmox and what their MAC addresses are – probably something I should have sorted out before doing anything else anyway.

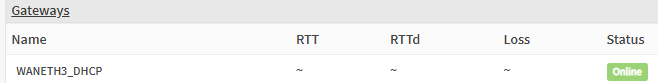

Once the router had a connection, everything ran great. For thirty minutes. After which, the router simply couldn’t talk to the gateway any more. No Internet connection.

In OPNsense’s dashboard, it indicated that EVERYTHING IS FINE. Which, you know, not true.

A reboot results in the same behaviour – everything is fine for around half an hour, then no WAN connectivity. Renewing the WAN connection fixes things… indefinitely. Until another reboot.

Thus began The Troubleshooting.

Various settings and configs were checked. IPv6 disabled (just in case), hardware VLAN filtering disabled etc etc

Same behaviour.

Install a completely fresh OPNSense VM – exact. same. behaviour.

And the whole time – once I renew the WAN connection, it fixes itself for as long as it remains up.

The command I ended up running in the shell:

configctl interface reconfigure wan

Magically fixed it… but only if it had already broken. That is, I couldn’t just run a renew at the end of the boot sequence and call it a day – I had to wait until the WAN connection failed before I could renew it – and that just didn’t fly (not that appending some magic words to a startup script would have made me happy).

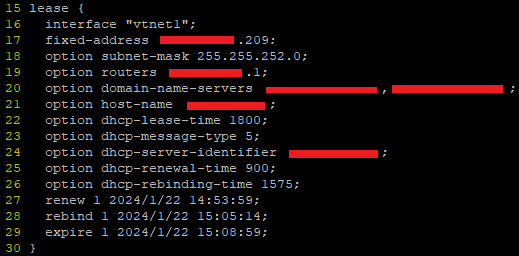

I ended up digging through the DHCP client leases file in /var/db (in my case dhclient.leases.vtnet1) and noticing some strange overlaps in the renewal/rebind/expiry etc times.

These leases files look like this:

Turns out, this a log, rather than a config – FreeBSD is writing the dates and times there as a record, not an instruction. But this was the clue to help figure it out – when router first booted, the lease file was written to but the time for renewal and expiry passed without the router even trying to renew the connection.

Once I reran the renewal command manually, it worked fine, but crucially, it was writing dates and times that were wildly different to the initial time on bootup.

Anyway, as with all things, it was DNS.

Well, sort of.

When I set up the initial Proxmox install, I somehow (?) managed to set its DNS server to be 127.0.0.1. Surely that can’t have been the default?

Anyway, that meant that while it could do all the work of creating VMs just fine, it couldn’t, among other things, talk to NTP servers to figure out the time.

But it did know it was in the UTC+8 timezone. And it did assume that the hardware clock was in UTC time. Which it wasn’t. It was set to local time. So my VM host believed it was 8 hours ahead of when it actually was.

When my router booted up, it was given this time and it then obtained a lease and made a note to renew that lease in 15 minutes. 30 minutes, tops.

But it then used an actual DNS server to do an NTP lookup for the correct time – at which point it said to itself, “hoo boy, I am 8 hours ahead of where I should be! Lemme just fix that right up.” But its lease now thinks the expiry is not for another 8 hours – hence failing to renew and not having any WAN connectivity.

To add to the confusion with all this – FreeBSD in all its wisdom writes dates and times to the lease file in universal coordinated time – not local time – without any indication that this is what it is doing. So when the router first obtained that lease and wrote the wrong time to the log, it looked to me like the correct time, but when I renewed the lease manually, it had corrected its own time and was now logging, what appeared to me to be 8 hours in the past.

Obviously, I think everything should always just be in UTC and that there are no problems or issues that would or could be caused by adopting a world free of timezones, but, please, indicate that somewhere, hey?

Anyway, OPNSense seems fine and good. I’ve managed to do some port forwarding and set up queues to minimise bufferbloat, so all is right with the world.

Now if I can just wrangle IPv6 DNS…