I’m talking to you, enterprisey organisation.

Your ITS people just got back from a seminar and they’re all fired up to enforce password changes every 3 months and allow your users to “take control of their accounts” by using “security questions” to reset passwords.

Well that’s dumb. Don’t do either of those things.

People are bad with passwords. They don’t understand security in general. Forcing them to change their mediocre passwords every 90 days instead of never is only going to exacerbate the problem.

Let’s take a look at my university’s policy:

- “A maximum of 16 characters” – Don’t do this. Don’t be this dumb. Once your password is salted and hashed, it doesn’t matter if it’s 16 characters or 216 characters. This isn’t 1988 and we’re not storing plain text passwords in a non 3NF database using COBOL. Stop putting low (very low) upper limits on password length.

- “A minimum of 1 upper/lower/number/special” – great, you’ve just narrowed things down for the guy trying to brute force a password (not that that’s how people break in these days anyway). How many of your people are going to put more than the minima you just set in their 8-16 characters? A negligible few.

- “The password can’t contain… spaces” – Don’t. Just… don’t. Do. This. Combined with the 16 character maximum above, this completely rules out using a passphrase (longer, easier to remember). There’s no backend reason to disallow spaces, which means you either have this rule because you heard it was the right thing to do (it’s not) or because you have a badly designed front end which breaks on spaces.

- Challenge questions

“Challenge questions” or “security questions” or “secret questions” or “giving out personal details to everybody for no good reason” were a kludge invented for a bygone era and are no longer useful or necessary.

In fact, they’ve been badly implemented since their inception, and were worse than useless even 7 years ago.

You might have seen in the news lately that a number of celebrities have had their iCloud accounts broken into and private photos stolen and distributed.

Why did this happen?

Well yes, because some people are complete assholes. But how it happened, dollars to doughnuts, is that many of these celebrities used questions to which the answers are not difficult to divine. It’s not their fault – they’re not the experts. You, enterprisey organisation, are. And if your security policy is only good against people who don’t actually know you, then it sucks.

See also, this blog post from iiNet.

Your password should be a minimum of 9 characters

Why 9? Is this a “You don’t have to be able to outrun the bear, just the slowest person in your camp” situation?

No white space

One character is just as good as literally any other. The only vaguely plausible argument I’ve seen to justify this is that passphrases will often have lower entropy than passwords – since people write predictable sentences as much as predictable words and sentences usually consist of fewer components (words vs characters).

Except, people who use passphrases don’t make them up. They have them randomly generated.

They’re also rare, so not worth trying to tackle.

Why is it silly to ask your users to choose meaningless strings of characters, especially in light of the fact they’ll have to change the damn thing in 3 months anyway?

Because your users can’t remember them. Many of your users don’t log in every day or even every month – the next time they log in might be to change the damn thing because 90 days are up.

So they tack a 1 to the end of their last password. Or if you forbid minor modifications (which you shouldn’t even be able to check, by the way!), then they write them down. Or both. Which defeats the purpose of your security policy, or in many cases is worse than just letting them keep the same damn thing for 8 years.

What’s the solution?

Use proper two factor authentication (no, security questions are not 2FA – at best, they’re half factor authentication).

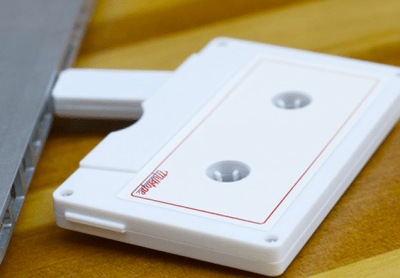

If you’re a company, issue dongles to your users. You can even re-sync them every 90 days if you like.

If you’re not, issue a key generation app for smart phones (or any phone that runs Java) or use an existing one.

Failing (or in addition to) that, you can SMS codes to your users’ phones. Even banks manage that much, and they’re basically the gold standard in doing this stuff badly.

You can also issue security certificates for your users to combine with their passwords. Issue a new one every 90 days or monthly or whatever makes you happy – it’s nothing new for them to remember, so they won’t care.

And fire the guy who does your ITS seminars.